- Punch List Architecture Newsletter

- Posts

- Our new architecture of campy imperialism

Our new architecture of campy imperialism

How the Arc de Trump unveiling soft-launched the Venezuela takeover

President Trump during a White House dinner on Oct. 15, holding a model of a planned “Independence Arch.” Asked later by a reporter whom the new arch would honor, Trump answered directly: “Me.” AP Photo/John McDonnel

One of the defining aspects of the second Trump presidency is the way it operates simultaneously on two tracks, one real and the other closer to cosplay. It’s fair to say, for example, that the administration’s takeover of Venezuela is an example of a rebooted American imperialism and, at the same time, a sort of hamfisted performance of colonial swashbuckling, cynical to the point of nihilism and manufactured for social media. The same could be said of the criminal charges brought in the U.S. courts against Nicolás Maduro: While they have kicked a genuine legal machinery into gear, an equally important goal for the administration is of course a show trial of the most cartoonish variety.

What matters in all of this is less diplomacy or democracy promotion (as if!) than a particularly warped kind of spectacle shaped especially for terminally online and easily distracted eyeballs. As Elizabeth Lopatto and Sarah Jeong put it in a terrific Verge essay this week, “The Trump administration is behaving like gambling addicts chasing clout in an attention economy. Venezuela is a fucking meme stock.”

The architecture of Trump 2.0 is in the same vein. It relies on bricks and mortar, on demolition and construction, on real-life labor. But it is meant to live more solidly, paradoxically enough, in the online ether, which means it gains significance as soon as any version of it, however slapdash or provisional, is posted on social media. And it grows more sophisticated and variable in its symbolism as it evolves from project to project—certainly not in terms of form or style but, instead, in its digital impact—outpacing the flatfooted attempts of legacy media outlets to capture and make sense of it.

And so, even as Trump’s plans for the White House continue to balloon in size and budget and generate fresh headlines, it has become clear that the project we really should have been paying attention to is the Independence Arch, better known as the Arc de Trump. This is the design whose unveiling foreshadowed the Venezuela takeover, after all—and tossed cold water on those early hopes, speaking of legacy-media outlets, that Trump would steer clear of foreign wars and nation building.

(Remember this column?)

The Arc de Trump is the design that most fully reveals the peculiar spin Trump wants to put on imperial ambition, which is after all the fundamental thing any triumphal arch is meant to symbolize.

It is very much on brand for Trump that we have only a vague idea of who designed it, since too clear a sense of authorship might begin to compete with the arch’s one true aim, which is to pay tribute to the president. If we are reviving notions of American empire, it’s worth always keeping in mind that the latest version is an empire of one. The arch is nominally meant to mark the 250th anniversary of American independence. But asked by a reporter whom or what it would honor, Trump answered directly: “Me.”

Considering the way the ballroom project has unfolded, moving from vaporous promises to IRL demolition of the old East Wing in a matter of weeks, there are two things about the arch that we can assume. One is that the chances of it being built are pretty good, and in a form that at least resembles the plans we’ve seen so far (though perhaps not in time for the semiquincentennial). The other is that when Trump uses architecture to soft-launch a turn in his approach to, say, foreign policy, we should pay attention.

So here’s what we do know:

During a dinner for ballroom donors at the White House on Oct. 15, Trump held up models of a triumphal arch that he said is planned for Memorial Circle, a traffic circle on Columbia Island, a 15-acre parcel under the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia, at the western end of Arlington Memorial Bridge.

The location is directly across the bridge from the Lincoln Memorial.

Columbia Island was created from river dredging for the construction of the bridge, which opened in 1932, and is within Lady Bird Johnson Park, which is itself a section of George Washington Memorial Parkway. A good history of the site is here.

Memorial Avenue, which travels over the bridge and into Memorial Circle, is part of a sequence designed by McKim, Mead, and White as the entryway to Arlington Cemetery. Memorial Circle itself, however, was designed not by that firm but by Gilmore D. Clark.

The models for the arch that Trump held up on Oct. 15, along with elevations that were displayed at the dinner, precisely match a design posted in early September on the Instagram and X feeds of the architect Nicholas Charbonneau, who is a principal at Harrison Design and runs the firm’s Sacred Architecture Studio from its D.C. office.

These images show a grand neoclassical arch flanked by paired Corinthian columns on each side and topped by a winged figure in gold, which Trump has said will represent “Lady Liberty.” (Traditionally, as in the Statue of Liberty, depictions of Lady Liberty don’t have wings.) Harrison Designs did not respond to a request for comment.

The Arch of Titus in Rome, a model for the Arc de Trump. As Mary Beard has written, the symbolic power of the triumphal arch traditionally went far beyond memorializing a particular imperial campaign. Carole Raddato via Wikimedia Commons

Is the arch design in earnest? This is where things get interesting. The answer of course is yes and no. Everything Trump does is, at some level, camp—he shares this trait with many authentic and aspiring autocrats—and therefore difficult to scrutinize without feeling a bit silly about the whole enterprise. At the same time, you could make a perfectly rational argument that building the Charbonneau version in Memorial Circle is very much in keeping with the neoclassical, City Beautiful sensibility of the larger McKim plan. Charbonneau, like the first ballroom architect, James McCrery, is one of the neotrad true believers whose work is gaining fresh credibility and attention in the second Trump administration.

Charbonneau’s posts followed an April essay by Catesby Leigh in The American Mind (a publication financed by the conservative Claremont Institute) calling for a “temporary Independence Arch” in Memorial Circle, to be completed by July 4 of this year and later replaced by a permanent version. Leigh’s essay featured sketches by Charbonneau of an arch design that has in the months since grown more muscular.

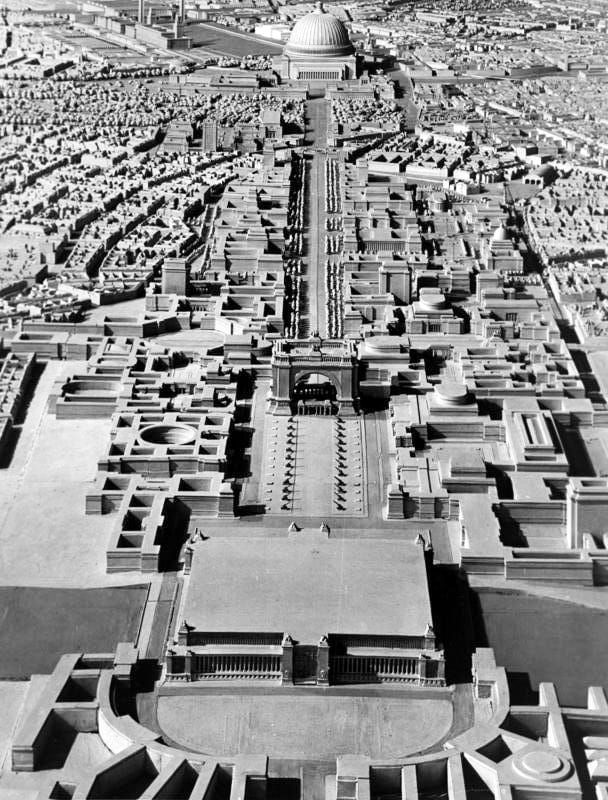

It's certainly true that triumphal arches in the modern era have had mixed symbolic parentage. Sometimes they’re built simply to mark anniversaries or remember fallen soldiers. Stanford White designed the Washington Square Arch to mark the centennial of the first president’s inauguration. Sometimes, as with Albert Speer’s plans for Hitler’s Welthauptstadt Germania, a plan for Berlin anchored by a grand Avenue of Splendors connecting the domed Volkshalle to a giant triumphal arch, the architectural and urban ambitions are less benign.

The Arc de Trump comes directly through the imperial line. It’s closely modeled on the Arc de triomphe in Paris, built by Napoleon to honor—well mostly to honor Napoleon himself, and secondarily his army’s victory at Austerlitz in 1805. (Construction began on his birthday the following year.) And the Arc de triomphe is of course an updated version of imperial Roman arches, most prominently the Arch of Titus. Those classical arches were the architectural culmination of the tradition of Roman triumphs, military parades in which the spoils of war and expanding empire were brought back within the city walls.

A model of Albert Speer’s plans, prepared for Hitler and only partly realized, for Welthauptstadt Germania, featuring a grand boulevard leading to a giant triumphal arch. Bundesarchiv, Bild 146III-373 via Wikimedia Commons

In that sense it would hard to believe that Trump’s plans for the arch have only to do reestablishing a neo-traditional national style and nothing at all with his growing hemispheric military ambitions. It’s become clear that those two goals can no longer be so neatly disentangled.

Catesby Leigh himself let the mask slip a bit (or maybe dropped a little crumb, an amuse-bouche for strongmen fans) when, in his April essay, he suggested the Independence Arch might be crowned by “an emperor-like Liberty figure.” As is so often true with Trump, especially the unbridled version who has emerged in the second term, the desire to build the arch emerges from a murky stew of vanity, vulnerability to flattery and persuasion, authoritarian impulse, and insecurity.

But can an arch really foreshadow or seek to build the case for, rather than simply memorialize, imperial ambition? This is in fact precisely how triumphal arches have operated from the Roman empire onward. As Mary Beard puts it in The Roman Triumph, her remarkable and highly readable 2007 study of this history, “The important fact is not that such arches regularly commemorated triumphs (though some did), but—in a sense, the other way round—that they used the imagery of triumphal celebrations as part of their own rhetoric of power.”

Camp or no, we should view the Arc de Trump—in its proposed form, and if it is ever realized—precisely through this lens.

News & Notes

Trump’s new ballroom architect, Shalom Baranes, appeared before the National Capital Planning Commission yesterday to present an updated design for the project. The drawings are decidedly more refined than what we saw from James McCrery but leave intact some of the earlier version’s missteps, like a portico shoved to the far end of one facade—the gesture that Peter Eisenman memorably called “untutored.” (Kriston Capps has a good roundup at CityLab.) The biggest news to come out of the hearing, the Architect’s Newspaper notes, was that Baranes and Trump are discussing adding a floor to the West Wing of the White House—in an effort, perversely enough, to match the scale of the enlarged ballroom. (Talk about the tail wagging the dog!) This lines up with details that emerged from the recent sit-down between Trump and a quartet of New York Times reporters in the Oval Office.

Punch List readers had some terrific suggestions for additions and amendments to last week’s book list to mark the American semiquincentennial. Michael J. Lewis, professor at Williams and architecture critic for the Wall Street Journal, whose biography of Frank Furness was on my list, recommended Living Architecture, James O’Gorman’s 1997 biography of H.H. Richardson, as well as Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer’s 1888 monograph on Richardson (“the first serious study of any American architect”). Wonne Ickx suggested Miami in the 1980s: A Vanishing Architecture of a Paradise Lost, edited by Charlotte Von Moos. John Parman wrote to say we should be on the lookout for a forthcoming book on Design Book Review (the critical journal published from 1983 to 2001) edited by William Littman and others. And Sam Wilson tagged Yasmin Khan’s biography of her father, Fazlur Khan of SOM, as well as Leslie Robertson’s memoir, The Structure of Design: An Engineer’s Life in Architecture. Keep these suggestions coming!

Jack Murphy’s meta-critical roundup of reactions to Foster + Partners’ new JPMorgan Chase tower on Park Avenue is very much worth reading, and not just because he describes Punch List as “pleasingly zingy.”

See you next week.

Punch List is published weekly. Subscribe free here, or sign up for a paid subscription, with bonus material, here.

Email: [email protected]

Reply