- Punch List Architecture Newsletter

- Posts

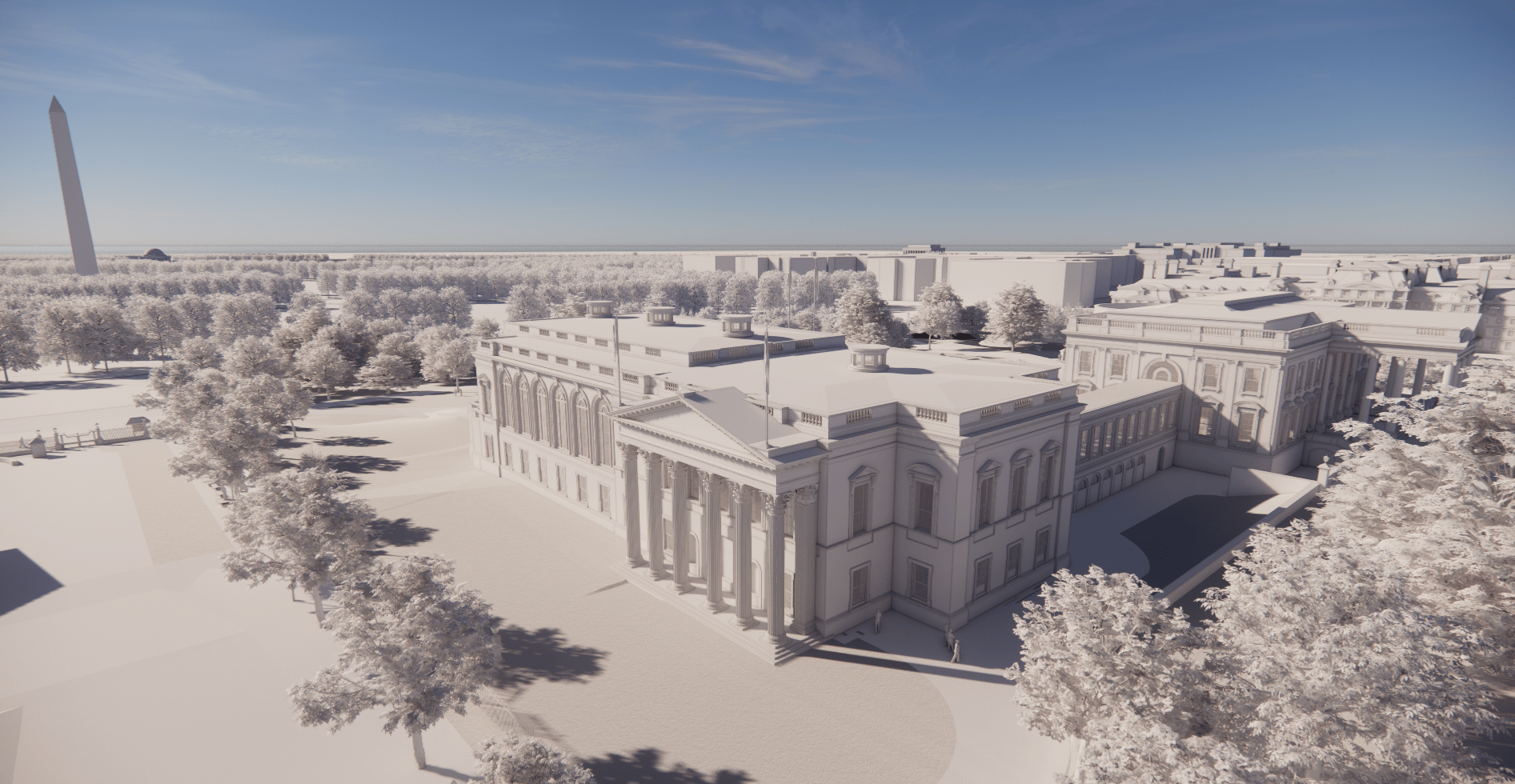

- What to know about James McCrery, Trump’s White House architect

What to know about James McCrery, Trump’s White House architect

And what Peter Eisenman, his former mentor, thinks of his ballroom plan

James McCrery and Donald Trump on the White House roof, Aug. 5. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

Late Tuesday morning, to the surprise of a group of reporters assembled in the garden below, Donald Trump appeared on the roof of the White House, atop the colonnade leading to the West Wing.

“Sir, why are you on the roof?” one of the reporters asked. Another, perhaps not hearing her colleague, shouted, “Mr. President, what are you doing up there?”

“Taking a little walk,” he answered.

“Why? Why?” the reporters chorused.

It went on like that. The episode did not leave me feeling especially optimistic about the condition of the Fourth Estate. But the “little walk” did introduce the world to Trump’s bow-tied rooftop companion, the 60-year-old architect James C. McCrery II, who is leading the design team (with AECOM and Clark Construction) on a controversial plan to build a 90,000-square-foot ballroom to replace the White House’s East Wing.

Gold-plated to the vanishing point: the interior of Trump’s planned White House ballroom

Together the two men strolled across the rooftop, occasionally huddling to talk while pointing in the direction of the Rose Garden, which Trump has paved over, obliterating Bunny Mellon’s Kennedy-era design in favor of an efficient hardscape. This week Trump filled the new plaza with tables, chairs, and striped umbrellas nearly identical to the ones decorating Mar-a-Lago, his Florida estate.

Until now the changes Trump has made to the White House, all of them redolent of his Louis XIV-meets-“Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” taste, have been either superficial (like the Rococo-adjacent ornament he’s added to the Oval Office) or relatively limited in footprint, like the Rose Garden revamp and the pair of flag poles, each nearly 100 feet tall, he added to the north and south lawns. But the scope of the ballroom plan, which has an estimated budget of $200 million and threatens to permanently disfigure the White House and its grounds, means that McCrery has become a figure of intense interest, both within and beyond the architecture profession.

Here’s what to know about McCrery, his surprising path to neoclassicism, and his ballroom proposal:

He studied under Peter Eisenman and Jeff Kipnis at Ohio State, in the 1980s. Not the usual proving ground for a traditionalist! This was after Eisenman’s stint directing the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York and as he was completing the Wexner Center at OSU. (Kipnis joined the OSU faculty in 1987.) In an interview earlier this year with Jan Bentz for the European Conservative, McCrery discussed his relationship with Eisenman at length, saying he’d “spent almost the entirety of my graduate education under his leadership and mentorship.” McCrery made a point to stress the “high regard I hold for him in my mind and in my heart.”

The ballroom exterior, looking southeast

He then worked for Eisenman’s firm in New York. Arriving in the office, McCrery told Bentz, “I thought, ‘Wow, this is just a little part of heaven. Everyone’s smart. You don’t have to start from the beginning; you can be in the middle of a sentence and they’re already with you, and you’re already with them.’ What a treasure.”

He made a major pivot to neoclassicism in the 1990s. Becoming disillusioned with Eisenman’s approach and with the larger category of deconstructivism, which he has said he loved for its rigor but grew to hate for its spiritual emptiness, he went to work for the classicist Allan Greenberg for six years. “Within two weeks of working for him I knew I was home,” McCrery said. He then began what he’s called a second course of study, this time in the classical tradition, “more of an atelier-like education. You appended yourself to the workshop of a master.”

He has described this shift, and his broader career arc, in religious terms. “God helps people understand what it is that His will for them is,” he said in the Bentz interview. “I truly believe that. It’s most efficacious when the person is open to that help, that guidance.” He has similarly dismissed modernist architecture as “ungodly”: “It’s exactly not created. It’s counter to God’s creation, in every aspect and in every detail.”

His own firm, D.C.-based McCrery Architects, has specialized in religious architecture. Its portfolio includes cathedrals in Tennessee, North Carolina, and Texas, as well as a Carmelite monastery in Wyoming. In recent years it has taken on a growing number of civic projects. This profile from the Catholic University website lists some of them, including a master plan for the North Carolina State Capitol grounds.

Trump appointed him to the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts near the end of his first term. McCrery served there from 2019 through last year.

His ballroom plan has already elicited a pointed response from the American Institute of Architects. In Trump’s first term the AIA was widely criticized for its accommodating approach to the administration. This time around the organization is taking a more critical stance. It issued a letter this week to the Committee for the Preservation of the White House, signed by Evelyn Lee, this year’s AIA president, and Stephen Ayers, its interim CEO and from 2010 to 2018 the Architect of the Capitol, raising alarms about several aspects of the ballroom plan. Though it is couched in diplomatic language, the letter calls out the administration for choosing McCrery without an open public process and raises questions about what it calls the design’s “scale and balance”: “We urge careful consideration of adjustments that would align the proposed additions more closely with the White House’s historic character.”

The ballroom would swallow up the existing East Wing and keep marching south

Susan Glasser, writing in The New Yorker, took a small bit of comfort in the fact that the ballroom proposal, along with recent comments from Trump that he might actually leave office in January 2029, when the Constitution requires him to, suggested that he was “beginning the long, slow pivot to legacy mode.”

McCrery declined to comment for this post. A spokesman from Touchdown Strategies, a strategic communications firm in Great Falls, Virginia, emailed to say that “James is not available to speak publicly in the short term.” But a couple of his former colleagues were willing to share some thoughts on the record.

Robert Livesey, who was chair of the OSU architecture department from 1983 to 1991, wrote in an email that “to be honest, I do not have a real memory of Jim. My sense was that he was a good design student which is why Eisenman hired him.” He added, “Unfortunately, his work does not have the presence of real classical architecture, or even of people who were also after the classical, like Palladio, or later Hawksmoor.”

Eisenman was pithier. He called McCrery’s ballroom design “bonkers” before adding, “putting a portico at the end of a long facade and not in the center is what one might say is untutored.”

A view looking east. Why the renderings provided by the White House make the trees and the ground plane white, to match the architecture, has not been satisfactorily explained

I don’t disagree with the growing consensus that the ballroom design, a big-footed architectural presence stomping toward the southern edge of the White House grounds, violates the very standards of beauty and proportion that McCrery loves to rhapsodize about in interviews, to say nothing of the protocols long in place to guide changes to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. I’m also of course reminded of the heavily gilded architecture that Viktor Orbán’s autocratic government coaxed from the typically more subtle Sou Fujimoto in Budapest, which I wrote about in Punch List #3.

In the end, though, the design’s larger meaning may have less to do with the style wars than with the unapologetically transactional posture of the second Trump administration. If the president succeeds in getting the ballroom built before he leaves office, as he’s said he intends to, the galas held there won’t be about national unity or cultural excellence, and the tickets for them, in ways literal and otherwise, won’t be free. It will be a place to kiss the ring, to bend the knee, and to pay for the privilege. What the design suggests is not so much a bloated classicism or an effort to turn Washington into Mar-a-Lago north, although it is both of those things, as a blueprint for making concrete the notion that the White House has turned in some fundamental sense into a retail outlet, a place where access and influence are nakedly bought and sold.

News & Notes

Two of the L.A. writers I respect most, Gustavo Arellano at the L.A. Times and Zocalo’s Joe Mathews, have published pieces in recent days arguing that Los Angeles should withdraw from hosting the 2028 Summer Games. For L.A. city leaders, Mathews suggests, putting on the Games will mean collaborating “with a lawless U.S. regime—and its rights-violating security apparatus—as it openly wages war against our city and state.”

In the New York Review of Architecture, Marianela D’Aprile reviews “Emergent City,” a documentary tracking battles over development and gentrification in Sunset Park.

Many thanks to Stefan Novakovic for interviewing me for the Canadian architecture and design magazine Azure, and for writing that Punch List “has quickly shot to the top” of his weekly reading list.

The best HR advice comes from those in the trenches. That’s what this is: real-world HR insights delivered in a newsletter from Hebba Youssef, a Chief People Officer who’s been there. Practical, real strategies with a dash of humor. Because HR shouldn’t be thankless—and you shouldn’t be alone in it.

Punch List is published weekly. Subscribe free here, or sign up for a paid subscription, with bonus material, here.

Email: [email protected]

Reply