- Punch List Architecture Newsletter

- Posts

- Where is Chinese architecture headed?

Where is Chinese architecture headed?

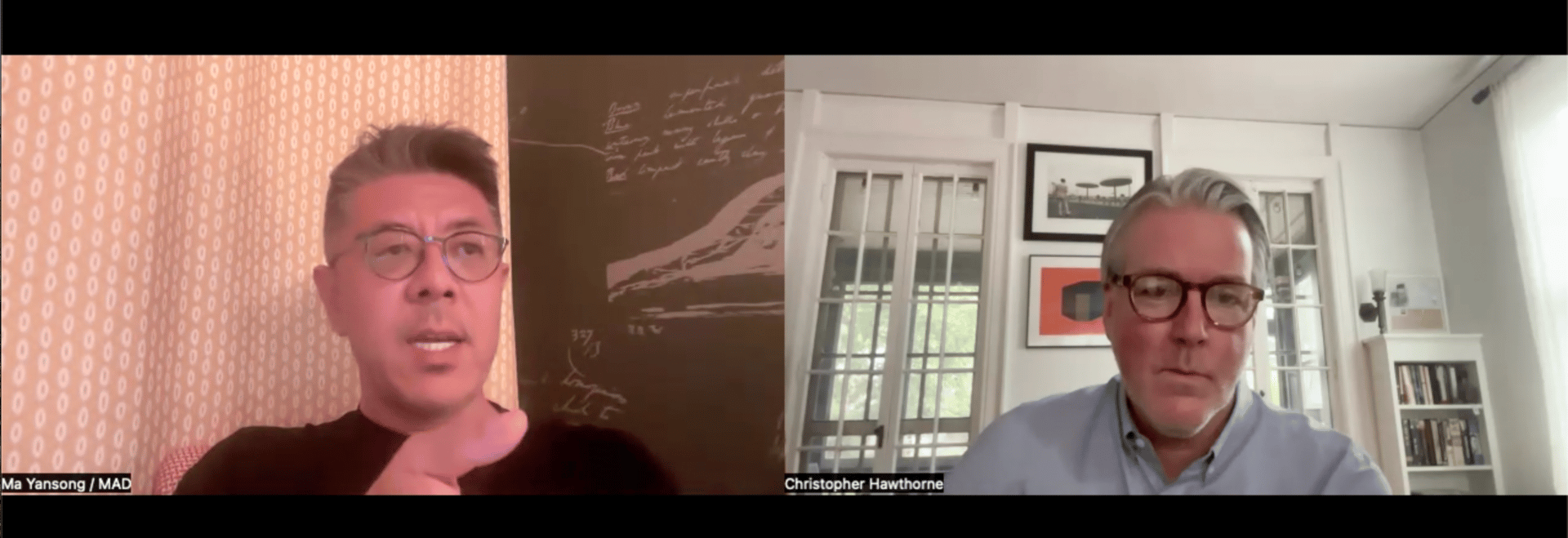

A conversation with Ma Yansong

Ma Yansong, center, inside the China Pavilion at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale. Photo by demone

Ma Yansong, born in Beijing in 1975, is without question the most prominent Chinese architect on the world stage. Educated first at Beijing University and then at Yale, where he earned a master’s degree in architecture, Ma returned to work in China and in fairly short order began landing large-scale projects around the country. In recent years he has also become the first Chinese architect of his generation to win a string of high-profile cultural commissions in Europe and the US, including the superb Fenix museum in Rotterdam, which opened earlier this year with a focus on migration, and the forthcoming Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles. In general the work of his firm, MAD Architects, is fluid, bold, and photogenic, drawing from Chinese traditional sources as well as organic forms but always, to one degree or another, abstracting them. He was my colleague on the Yale architecture faculty last year, where he served as Eero Saarinen Visiting Professor of Architectural Design. (Maybe in some future Punch List I’ll tell the story of sitting on the final review for his Yale studio, which focused on Los Angeles, and where my fellow jurors included Peter Eisenman, Francis Kéré, Francesca Hughes, and Thom Mayne, among others.) Our paths crossed again this year inside the Arsenale at the Venice Architecture Biennale, where my project, Speakers’ Corner, a collaboration with Florencia Rodriguez and Johnston Marklee, is located not far from the China Pavilion, which Ma curated under the title “Co-Exist.” (The Biennale runs through Nov. 23.) We sat down via Zoom the other day to talk about his work and where he thinks Chinese architecture is headed. Because he used the China Pavilion to put a spotlight on emerging firms, with an age range of roughly 25 to 40, our conversation focused to a large degree on the situation young Chinese architects find themselves in at the moment, as the country’s economic growth slows and cities reckon with more than a decade of overbuilding. What follows has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Christopher Hawthorne: How did you decide to come to Yale to study? What was the state of architectural education in China at that point?

Ma Yansong: When I was in architecture school in China, I read a lot of magazines showing so many interesting projects that were very different from our studios. Chinese architecture school mainly focused on modernist architecture. So, Frank Gehry’s architecture, for example—we’d never study that in school. We only got to see it in magazines. So part of going to school abroad was a way to see more and understand more. Now, because of social media, people are already so familiar with architecture. So I don’t think school is how young people understand the world.

I’m sure there are students who ask you all the time about where to study architecture, and whether to go abroad. What kind of advice do you give them?

Architecture school in China is still very much focused on and within the profession, which I don’t think is right. I think architecture should go beyond the profession. In China we talk quite a bit about tradition, about old architecture. And we have a 5,000-year history. But what’s our relation to that? And to the future? You know, AI, technology, that’s such a big topic in China. It seems everyone is talking about the future, and technology. Architecture is so old-fashioned by comparison.

The Fenix museum in Rotterdam, which opened earlier this year. Photo by Hufton+Crow

I remember when I first started traveling to China to write about architecture—this was in the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics—there was a very intense debate about the decision to invite foreign architects to design the most significant symbols of the 21st-century city. I'm thinking of projects like the Olympic Stadium, of course, but also CCTV and others. How has the thinking about them evolved since 2008?

When it comes to the Olympic projects, there was a positive side: You had a diversity of architectural approaches. Some people said Beijing had become an experimental field for architecture. I think the real reason that Chinese architects criticized that group of projects was not just because they feared new architecture but because they were weak. The Chinese architects before that period had learned from the Western masters. They had no freedom to play beyond that. I think local architects are okay now that international designers work here. That wasn’t the case before the Olympics. But the other issue is confidence—the ability to create new architecture. In that sense, we are still weak.

Why do you think that is?

Education. It hasn’t changed enough, even in the current generation. There’s still a philosophy in China that architecture should just be usable, functional. People have a hard time understanding that architecture is an art.

Does this affect how your work is seen in China? Are you seen as a Chinese architect who went away and learned a different method in the West?

I’m quite special, in my generation. My generation was the turning point. We were the last to be really lucky in terms of the number of projects available to us as younger architects. I was thinking the younger generation coming up now would continue [this trajectory]; but the thing is, after me, the opportunities have shrunk, and the country has become more conservative.

Why do you think things have gotten more conservative?

The economy is one reason. Politics is another. China has been trying to promote tradition more. As a result, in China—not only in architecture but also in the social and cultural scene—younger people now are trying to attack older people, because they belong to the older values, and young people don’t buy into that anymore. Cai Guo-Qiang, the artist, just had this kind of trouble. He had this big firework display two days ago in the Himalaya Mountains. And the whole country is attacking him, including many from the younger generation, because of environmental [concerns]. The younger generation is very unhappy and unsatisfied with this conservative environment. So that’s the main reason I wanted to use the China Pavilion in Venice to give an opportunity to younger architects.

How did you go about selecting the group that you ultimately chose? What was your process?

I had a hard time selecting them because there are so many strong younger practices to choose from, and they have so many different interests. So even in our show it’s difficult to have a theme.

At the beginning I wanted to focus on the future, but the pavilion historically has been used to promote traditional values. And I thought, well, maybe that’s another way to look at the future, if you have some inspiration from the past. But we were clear that we didn’t want any visual elements, or references, to traditional architecture. We wanted to focus on real, contemporary issues. I think that’s one reason the government commissioned me, because they realized the way they were telling the Chinese story before in Venice wasn’t so successful. Nobody understood what they were talking about! So we tried to change the way we presented the contents.

Were these firms you already knew?

Some of them. And then we also asked some friends, media, critics. And we created a bigger list, and we talked to each of them, to try to understand their work. And we put them into categories. In the end we have these three sections: talking about the contemporary integration of tradition; construction; and then the future. Twenty years ago, you wouldn’t have any architects in China talking about the future in this way.

Is their attitude toward the future an optimistic one, or more anxious?

I see both. The younger generation is very critical of the way older architects have handled the question of sustainability and the environment. And other young architects are interested new technology, and how it will change their lives. Some of them see that as more important than architecture.

How do they see artificial intelligence and its relationship to architecture?

One of the firms in the pavilion is called People’s Architecture Office. They are thinking about the city from the bottom up. In their project [“Renew City Plugins”] they insert small elements into the existing urbanism, to provide new functions and make the city livable. This approach is quite new, because historically China has been a top-down society in a very strong way. They are working with a professor at Tsinghua University who is using big data and AI to prove that Chinese residential buildings are nearly half empty. The real-estate industry built so much—they’ve stopped building, but it’s already too much. And many buildings, especially in secondary cities, are empty. The architects have tried to propose how to use those empty buildings.

The younger architects you’re featuring in the pavilion are part of a generation that came of age during a period of intense growth and urbanization—and, as you say, overbuilding. How do they think about this period, and about the state of urban design in China?

They see many problems. They are largely working at the level of detail, at the level of smaller improvements. They cannot do big things. Before architecture has not many connections to people. It was so abstract, these big urban developments. Big, big objects. Now it’s more related to real needs. People care more about inner values.

The poster for this year’s China Pavilion, organized under the theme “Co-Exist”

Does that translate into an interest in interior or domestic projects?

Yes, as well as reuse and public space. I think this is similar to the US, but even more of a change in China.

To be a young architect with large-scale built projects, as you were, is exceptionally rare. Much more typical is the situation the firms in your pavilion find themselves in, where an exhibition becomes an opportunity to explore certain ideas, or gain notice, while building a practice.

Yes, that’s true. And it’s related to the economy. But I also think there’s something closer to the opposite happening. Twenty years ago, many architects, even if they were busy, they weren’t confident. They didn’t know what they were doing. They were just doing a version of what foreign architects were doing.

And now it’s an inversion of that? They have more confidence but less work?

Yes. They have more time to think. Also, culturally, the whole younger generation—not just architects—it seems they have a clearer idea of their position in the world and what they should do. And so they have started to set their own agenda. Before, there was nothing. Twenty years ago, if you said, “We should modernize China,” people understood that to mean one of two things. Either we copy the West or we’re against that and we should do something “Chinese.” Now the thinking is so diverse. Younger architects can say what they believe.

It sounds as though, while opportunities may be scarce in China, this generation of architects might be in a good position at some point to do work outside of China. Because they have a strong sense of what they’d like to accomplish.

If you look at the Japanese, it’s similar. They also don’t have many domestic projects, but they are quite influential internationally. This is because they have clear values in their architecture.

What do younger architects, and maybe younger members of the public, think of those Olympic-era projects? What do they think of CCTV, or the Olympic Stadium, or the Water Cube?

They criticize what they see as the specific weaknesses of those projects. And ignore the newness those projects brought to our society. They don’t feel the need to talk about that part, because they grew up in the midst of this openness.

They take that as a given.

So they might criticize CCTV, for example, for using too much material, too much steel. Or criticize the interiors for not being humane. Things like this—very detailed critiques that also show their approach. How they’d do things differently if given the opportunity.

It sounds like a fairly nuanced reading, actually.

Yes.

The China Pavilion’s “Concrete Spolia,” by [S] Equilibrium Lab. Photo by demone

What were your specific curatorial goals with the pavilion? How did you want to use the space?

I just wanted it to be one big room. I always have this trouble understanding architecture shows, because there are so many big objects and so much material. And in this case you have to ship all of it to a small island in Italy! So we tried to limit that. Every project we tried to limit to a certain weight. Most of the projects on view are very simple and very light. But one project (“Concrete Spolia,” by [S] Equilibrium Lab) is about reused concrete; it features a technology to cut structural concrete from existing buildings and reassemble it to create new architecture. So we found a factory in Venice that was being demolished. And they bought a concrete column from them. That was nice, I think. Overall, if I had another chance, I would do less. I think making a strong statement with less material is smarter.

My project at the Biennale, not far from the China Pavilion, is a collaboration with Florencia Rodriguez and Johnston Marklee that is in part an exploration of architecture criticism and its future. What is the state of criticism, and architectural media, in China? You mentioned the role of social media earlier. Are there younger writers, for example, making an impact?

There are a couple, but they are also using social media as their base, their outlet. Academically, they’re not so influential. Also, they’re not harsh. In China, there is a small circle of architects and critics, and they don’t want to really criticize one another. There’s not much healthy criticism.

Do you think there’s potential for it to emerge?

I don’t see it. There’s too much emphasis on relationships. When people finish a project, they invite only their friends to write things. Within the architecture profession, it’s really weak. No real criticism. Of course online people feel very free to criticize. There’s a term—they call them internet judges. There was a well-known older Chinese director who released a new movie and it totally failed—nobody wanted to see it. I went to see it. It’s not bad! But younger people think it’s so proud of itself, and they hate it for that. They think a movie like that just wants to show off. I think this will really start to have an effect. I think the culture will change to something more humble and more down to earth.

Do you think architecture in China will become more humble too?

I think so. People online are really discussing how much money each project is going to cost. Two of my own projects were withdrawn by the government, because they were afraid that this would become a public topic. I told them I could do it more cheaply, but it’s not really an issue of money. They just don’t want things to look a certain way.

Optics! We call that optics.

Punch List is published weekly. Subscribe free here, or sign up for a paid subscription, with bonus material, here.

Email: [email protected]

Reply