- Punch List Architecture Newsletter

- Posts

- Monumental hypocrisy?

Monumental hypocrisy?

When it comes to fraught histories, there are some questions that the left shouldn’t be afraid to confront

A city worker prepares to remove the statue of Christopher Columbus from New Haven’s Wooster Square Park on June 24, 2020. Peter Hvizdak/Hearst Connecticut Media; digital license via AP

This is the story of two removals.

Last Saturday night, a few hours before the arrival of what became known as Winter Storm Fern, I joined a sizable crowd at a hybrid museum and performance space called Lost in New Haven to hear Ionne, an electronic musician who describes his work as “futuristic, spiritualized, polarized, and polarizing—or at least thought provoking,” with a jazz duo as the opener. Looming over us from one side of the stage, with a globe in his left hand and a compass in his right, was a larger-than-life bronze statue of Christopher Columbus, installed in New Haven’s Wooster Square Park in 1892 and taken down in June 2020 by city officials near the height of the George Floyd protests.

Three days later, on a bitterly cold afternoon in Philadelphia, I crunched through Fern’s snowfall to visit the Independence National Historical Park. The park features displays about, and a partial excavation of, the so-called President’s House, where George Washington and then John Adams lived between 1790 and 1800, after the nation’s capital moved from New York to Philadelphia and before it was relocated to Washington, D.C. Earlier this month, the Trump administration, through the Department of the Interior, ordered the removal of a series of panels, added to the site in 2010, that detailed how much of the house’s daily operations relied on the labor of enslaved people, nine of whom were owned by George and Martha Washington. The city has filed suit in federal court seeking to force the administration to restore the display.

These two experiences were of course far from identical. In New Haven I found myself in the presence of a statue that had been removed from a civic square and reinstalled in a privately run but publicly accessible venue, alongside a diverse range of displays about the city’s history. In Philadelphia I was seeing empty spaces where historical markers had been taken down, in line with the Executive Order Trump issued in March of last year taking aim at federally operated sites that “inappropriately disparage Americans.”

A section of the President’s House installation, at Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, from which panels on slavery were removed last week

I was nonetheless struck by how much, at least in symbolic and thematic terms, the two settings overlapped. Perhaps another way of saying this is that I have felt, as this week has worn on, a nagging sense that my outrage about what happened in Philadelphia (and Fort Sumter, and the Smithsonian, and the Kennedy Center) is somehow complicated, or ought to be, by the story of how many statues, monuments, and memorials were taken down, in this country and elsewhere, in a wave of progressive activism that peaked between 2015 and 2020.

I took part in some of that activism, after all. In my own case, grappling with these questions brings back memories of efforts I helped lead when I worked in the Mayor’s Office in Los Angeles, most notably the policy recommendations produced, in a book called Past Due, by the Civic Memory Working Group we convened in City Hall in 2019 and 2020. The charge we gave the Working Group, which included historians, artists, architects, curators, and Indigenous leaders, as well as a number of my colleagues in city government, was “to produce a series of recommendations to help Los Angeles, so long in thrall to its reputation as a city of the future, engage more productively and honestly with its past—especially where that past is fraught or has been buried or whitewashed.”

The final recommendation, on our list of eighteen, read as follows: “Develop strategies to recontextualize outdated or fraught memorials as an alternative to removal—although removal will, in certain cases, remain the best option.”

The cover of the 2021 Past Due report, with recommendations from the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office Civic Memory Working Group. Design by Polymode; cover image by Scott Reinhard

Were we responsible for having pried open the very Pandora’s box that many of us on the left are now desperate to slam shut? Is this simply a basic question of power? That the faction in office removes the public monuments its supporters find offensive, or painful, while protecting the rest? Our Working Group, and ultimately the mayor, Eric Garcetti, had emphasized the need for alternatives to removal, yes; but we had also endorsed the idea that public agencies will sometimes be justified in taking memorials and monuments down. Rereading that final recommendation today, in the light of what the Trump administration is doing, I find myself wishing we’d sharpened its language a bit, replacing the phrase “in certain cases” with “in very rare cases.”

In one crucial way, though, the two cases are fundamentally different—to an extent that makes efforts to conflate them intellectually disingenuous. The central goal of that earlier wave of removals and reckoning—whatever its excesses or missteps—was to broaden the historical lens, to tell a fuller story of American history, and to incorporate overlooked or marginalized perspectives as well as new scholarship. I think even the most aggressive self-appointed critic of “wokeness,” if he’s being honest, would have to concede that point.

Even as we sought to grapple more directly with violent or fraught episodes in L.A.’s past—including the 1871 Chinese Massacre, whose victims are getting a long-overdue public memorial—we were equally open to finding space to honor celebrations of various cultural, political, and scientific histories. (These included the story of the room at UCLA from which the first internet message was sent, the parade that delivered the Space Shuttle Endeavour from LAX to its new home near USC, and the spontaneous remembrances of the rapper Nipsey Hussle that popped up in the Crenshaw district following his death.) Our interest was not to foreclose any particular telling of the city’s evolution but to acknowledge how many points of view had been sidelined in the top-down production of official monuments in L.A.

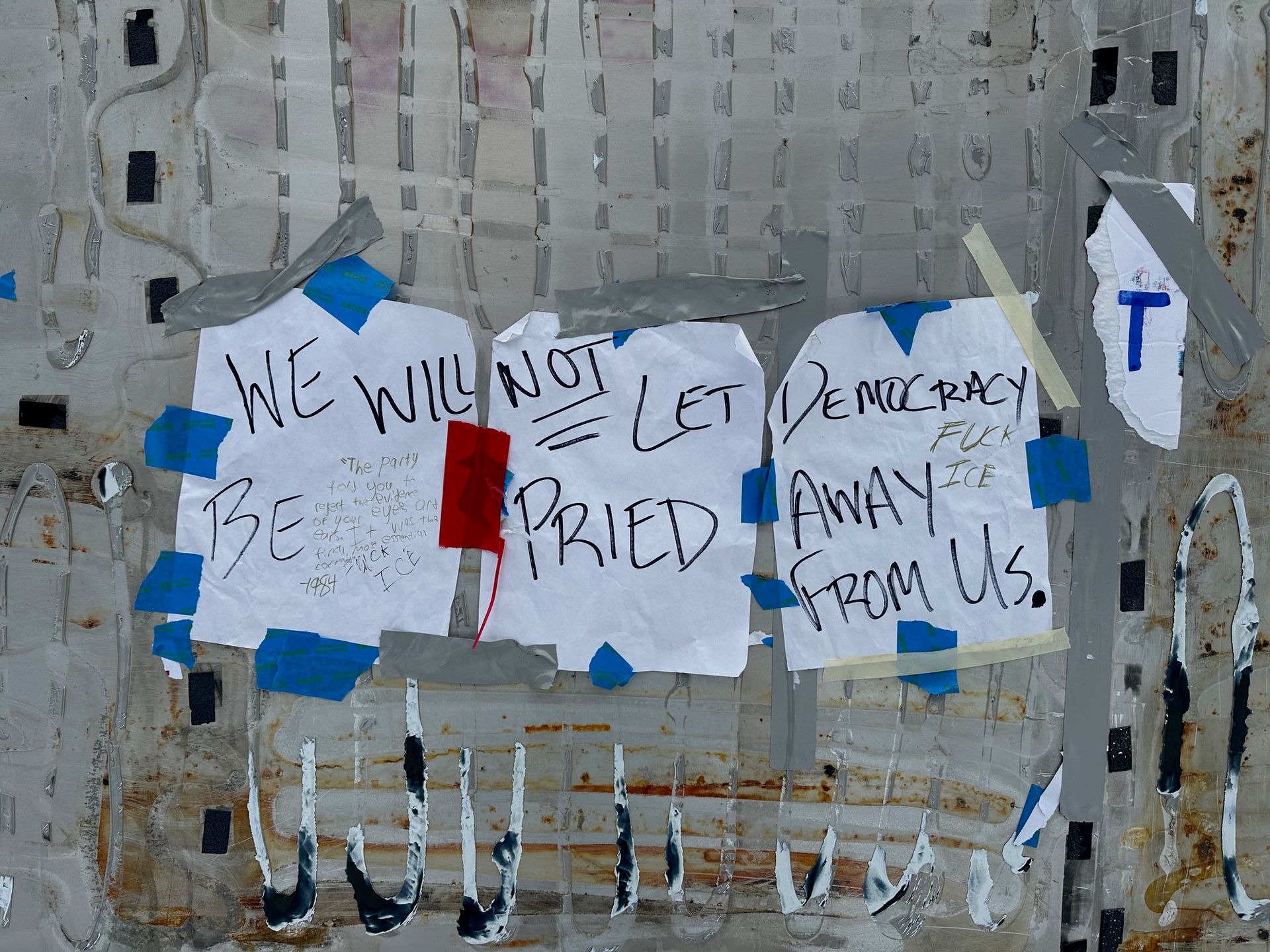

A sign taped to another section of wall at the President’s House from which panels were removed

The campaign led by the Trump administration, by its own telling, seeks to limit the historical narrative, and to put certain guardrails back in place along its edges. The March 2025 Executive Order seeks “to ensure that all public monuments, memorials, statues, markers, or similar properties within the Department of the Interior’s jurisdiction do not contain descriptions, depictions, or other content that inappropriately disparage Americans past or living (including persons living in colonial times), and instead focus on the greatness of the achievements and progress of the American people or, with respect to natural features, the beauty, abundance, and grandeur of the American landscape.”

Greatness, progress, beauty, abundance, grandeur—these qualities are meaningless if we rule out any acknowledgement of their opposites, or of the cost of achieving (or protecting) them. Imagine a novel, film, or song that tries to express joy without access to tonal registers like pain or sorrow. The whole enterprise quickly falls apart—becomes a parody of itself. Anyone who has practiced civic architecture understands that a blanket rule requiring only uplifting messages in monuments and memorials is a perversion of how design work operates, at least the good-faith and meaningful kind.

What we’re left with, given these new rules, is a public realm that begins to resemble a kid’s wind-up toy: pull the string to hear the joyful expressions of faith in the nation and its leaders, past and present, pour out. (Trump’s planned “National Garden of American Heroes” follows the same logic.) Truly it’s not far from there to Dear Leader recitations in other aspects of public life. Meanwhile the only additive aspect of the Trump administration’s campaign against public history has been to add the president’s name to venues like the Kennedy Center.

These debates, when it comes to the “appropriate” tone or sensibility of public markers and monuments, in particular to the question of whether they are sufficiently celebratory or patriotic, are of course nothing new. Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial was widely criticized even before its completion in 1982 for an overly dark reading of the war, with detractors calling it a “black gash of shame.” In fairly short order a traditional, figurative monument, “Three Servicemen,” was added nearby. I have written about a similar dynamic in play at the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan.

Another stark difference between the first wave of removals and the current one has to do with deliberation and the value of open, complex debate. Many of the groups leading the earlier efforts to reckon with fraught histories—even as they acknowledged and sometimes amplified the anger of activists who wanted to tear down statues of Columbus or Confederate leaders or, on the West Coast, of Junípero Serra—became models of patient, expansive public engagement. Monument Lab, based in Philadelphia, is one of several remarkable examples.

One central goal of our Civic Memory Working Group was to convene respectful but frank and wide-ranging discussions about the trickiest corners of L.A. history, starting with the legacy of Serra, a priest and missionary canonized by Pope Francis in 2015 even as he remains a symbol of pain and oppression for many Indigenous residents of California. The roundtable we organized on Serra included an artist and activist who helped topple a Serra statue in Los Angeles, Joel Garcia; two historians of the American West (including arguably the leading living expert on Serra, Steven Hackel); three Indigenous leaders; and Father Tom Elewaut, pastor at Mission Basilica San Buenaventura Catholic parish.

Our simple guiding thesis was that Angelenos would benefit from understanding more about Serra, not less. And it was Father Elewaut who struck a tone of compromise and reconciliation, directly acknowledging Serra’s legacy as “painful” for Indigenous communities and endorsing the removal of Serra statues within certain parameters:

I was recently appointed as the director of historic mission sites for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. This is a liaison position, and my obligation is to be in direct contact with Indigenous representatives about any changes being contemplated to mission lands or buildings. I am also committed to helping preserve Indigenous culture and cultural practices in all ways that I can. Slowly, little by little, we are making progress, and respect is our foundation. We have dialogues and discussions about ceremony, about Saint Serra. We all came to a respectful and I think correct decision to bring down the statue of Saint Serra. It was a painful matter for the Indigenous people of our region, and we wished the statue to be treated respectfully and not come down through violence.

This approach is not so different from the wide-ranging conversations that led to the removal of the Columbus statue in New Haven, as controversial as that decision remains among some of the city’s Italian-American residents.

In that spirit, I think it’s useful to confront head-on current charges from the right that progressives are guilty of hypocrisy when it comes to the removal of monuments and memorials. In Los Angeles, at least, when we said we wanted to “develop strategies to recontextualize outdated or fraught memorials as an alternative to removal,” we meant it. And even where statues were toppled or removed in the wave from 2015 to 2020—in New Haven, Los Angeles, and elsewhere—the open spaces and empty plinths left behind were often filled with new expressions of collective memory and local history, in many cases more thoughtful, inclusive, or nuanced than what they replaced.

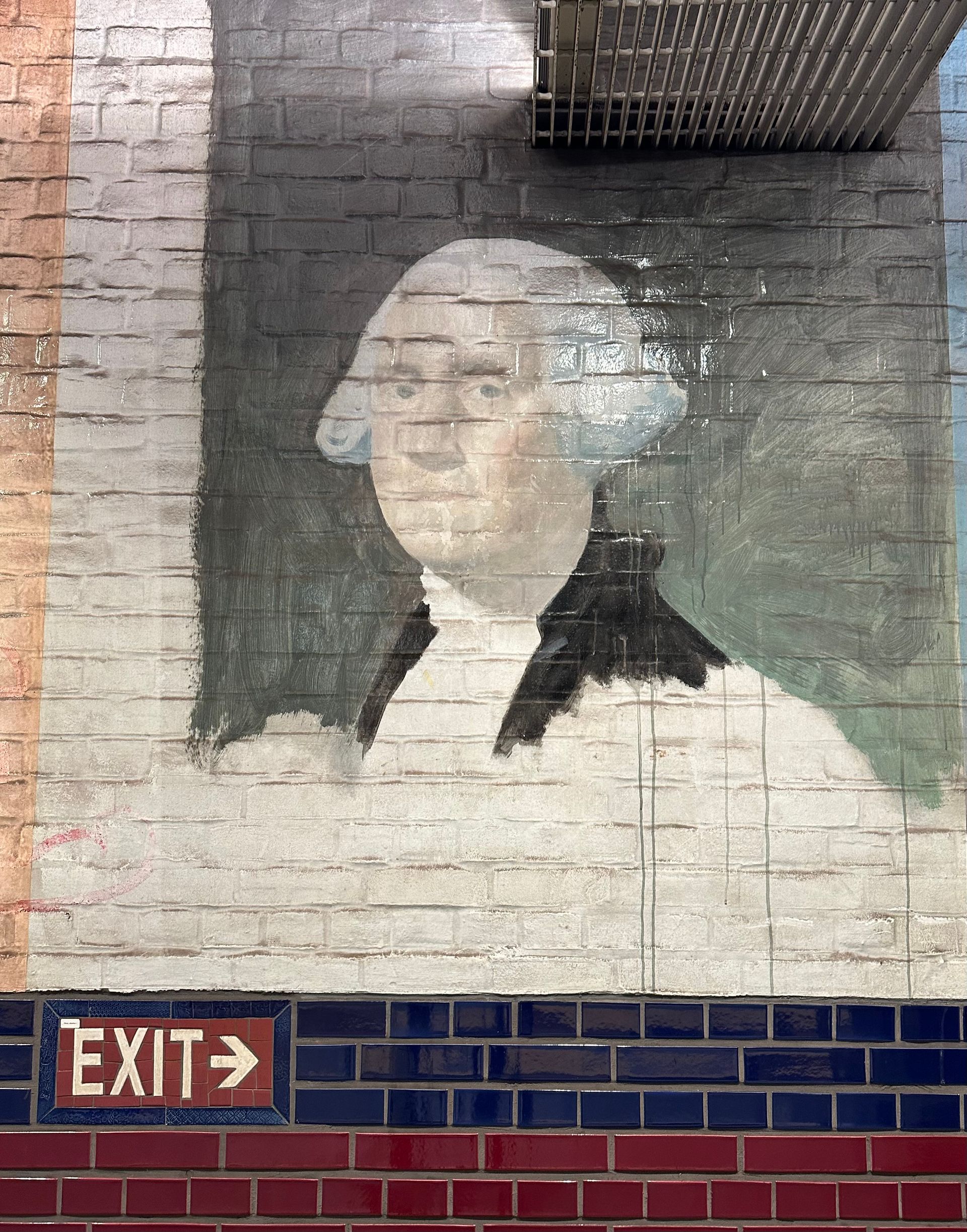

An image of George Washington in Philadelphia’s 5th Street SEPTA station, part of a larger installation by artist Tom Judd

What happened in Philadelphia was something different. The panels that had been added to the President’s House display—themselves an example of an approach to public history that supports adding rather than removing context, not to mention the products of years of local activism—were clearly ripped out in haste, with the loops of dried glue that held them in place now exposed to view. Absent a court order, I would put the chances that the panels will be replaced while Trump is still in office with thoughtful new reflections on civic memory, or on the relationship between slavery and American democratic values, at precisely zero.

The President’s House, as it looks now, can be accurately described as scarred. And it is stirring up some raw emotions. Taped to the wall where one of the larger panels had been hanging, I saw a hand-drawn sign reading, “We will not let democracy be pried away from us.” Just after snapping a picture of that message, I came upon a man in tears. Another man walked up two minutes later, fuming and cursing under his breath. “We are going to need a national holiday when this fucker…” He trailed off, but it wasn’t hard to guess who he was talking about.

Just steps from the removed panels, though, was a clue that the efforts to reframe and expand our understanding of American history that took place between 2015 and 2020 planted deeper roots than the current administration may realize—that what has been excavated and made public is not so easily reburied. The names of the nine slaves owned by George and Martha Washington are etched in a nearby granite wall.

It would take a tool sharper than the ones workers used to take down the slavery panels (some of which seemed to nearly peel off) to hack those names into unintelligibility. I wouldn’t put it past the Trump administration to send in another crew to try.

But for now the names remain, in a dignified serif script:

Austin

Paris

Hercules

Christopher Sheels

Richmond

Giles

Oney Judge

Moll

Joe

Punch List is published weekly. Subscribe free here, or sign up for a paid subscription, with bonus material, here.

Email: [email protected]

Reply