- Punch List Architecture Newsletter

- Posts

- Let them eat statuary marble

Let them eat statuary marble

How much of an electoral price did the GOP pay this week for Trump’s White House demolition spree? Plus: Mark Lamster on the threat to I.M. Pei’s Dallas City Hall

The new Lincoln bathroom. Via Truth Social

We’re joined this week by Mark Lamster to hear about a serious threat to I.M. Pei’s Dallas City Hall.

But first: some quick thoughts on Tuesday’s electoral Blue Wave and its relationship to architecture—specifically, to Donald Trump’s aggressive and ongoing remake of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, a campaign that has expanded to include the Lincoln bathroom.

Among centrist Democrats, libertarians, and sober-minded conservatives, there’s a certain kind of self-styled free thinker who secretly—and sometimes not so secretly—thrills to Trump’s more destructive behavior. Members of this tribe rallied around a particular talking point this week: Whatever you do, don’t even hint that maybe the president’s decision to take a wrecking ball to the East Wing of the White House to make room for a giant golden ballroom was an exceptionally dumb thing to do, politically speaking, in the run-up to the first consequential elections of his second term.

Instead it should be seen, as Ross Douthat put it in the New York Times, playing architecture critic for the week, as “a small example of why Trump’s bull-in-a-china-shop approach appeals; the president’s eagerness to pre-empt objections and just do something that seems necessary is part of why voters find him attractive.”

On Tuesday night, as the results came in from New York, New Jersey, Virginia, and California, revealing an electorate that seemed in a range of ways determined to stick it to Trump as the federal shutdown grinds on—rather than, pace Douthat, provide support for his more preemptive tendencies—the contrarians dug in their heels. Reason’s Robby Soave, in a post on X that the Atlantic’s Caitlin Flanagan was quick to share and cheer on, summed it up this way:

Omg, MSNBC once AGAIN said this result is a referendum on Trump's decision to renovate the East Wing of the White House. (Nicole Wallace this time.) You could not ever convince me that a single real voter cares about this, let alone opposes it.

— Robby Soave (@robbysoave)

2:29 AM • Nov 5, 2025

Omg, Robby! This was little more than a caricature of the argument Wallace and others were actually making. Their point was not that Tuesday was a referendum on the White House demolition specifically but, instead, that all those pictures of piles of rubble where the East Wing used to be have underscored a growing sense that Trump thinks of himself, like some baggy-suited combination of petty despot and Mob boss, as untouchable. And that he views the White House as his personal playground, to raze, gild, or emmarble as he sees fit.

The president only bolstered that sense by hosting a Great Gatsby-themed ball at Mar-a-Lago on Halloween night—and by announcing, just four days before Election Day, that he’d added the Lincoln bathroom to his list of architectural conquests, giving it a makeover that brings to mind Maurico Cattelan’s “America,” an artwork in the form of an operable toilet made of 18-carat solid gold, while on an aspirational scale ranking somewhere between a Grand and a Park Hyatt:

As one Times reader wrote in response to Douthat’s column, “This is not about a ballroom. This is about a President who does whatever he wants. There is zero oversight. No checks and balances.”

Exit polling supported this point of view. CNN reported that in Virginia, New Jersey, and California, where Democrats saw the biggest gains Tuesday, a majority of voters saw their ballots “as sending a message to Trump.” (And that message was not, by any means, “Knock more things down!”) Meanwhile specific polling on the East Wing demolition has found that voters disapprove of the ballroom plan by a wide margin: 61 percent to 25 percent in one poll, 56 to 28 in another. Add those numbers to the images of the Gatsby party, and of growing lines at food banks around the country, and it’s not much of a stretch to argue that Trump’s “let them eat statuary marble” attitude of the last several weeks added to the size of Tuesday’s Blue Wave. It certainly didn’t help the president or his party.

Maurizio Cattelan, “America” (2016), a fully functional toilet made of solid 18-karat gold, as seen at Sotheby’s at the Breuer, where it will be up for auction Nov. 18. Photo by Samuel Medina

On the subject of presidential architecture, I’m grateful to Christopher Beam of Bloomberg Businessweek for including me in this roundup of critical attitudes about Trump’s ballroom and Barack Obama’s Presidential Center in Chicago, due to open next year.

On the heels of Zohran Mamdani’s election as New York City Mayor, meanwhile, it’s high time to re-up this Punch List essay from June on his campaign’s remarkable design strategy.

And now to Mark Lamster, with some alarming news from Dallas.

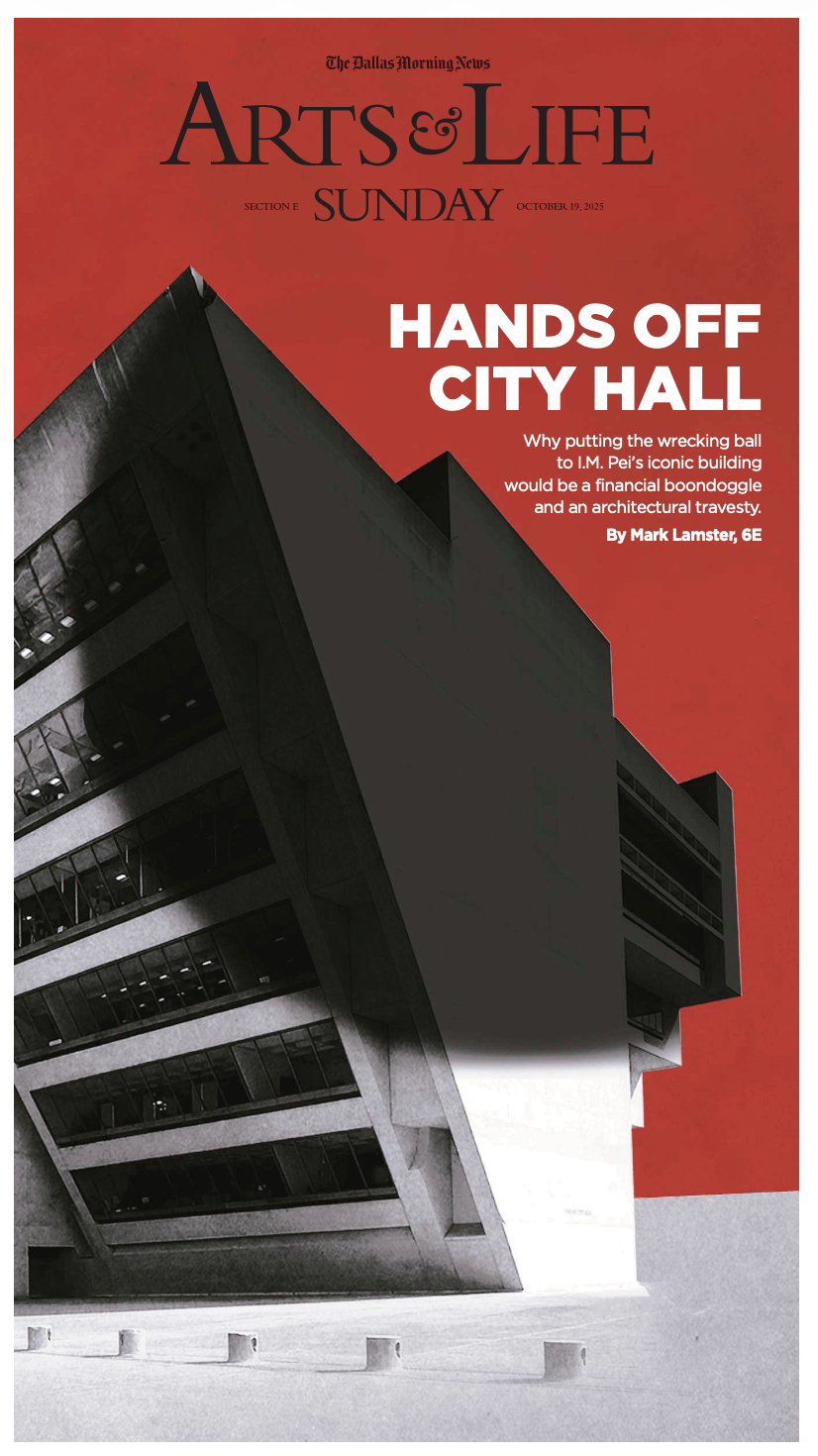

In early October, the news pages of the Dallas Morning News, where Lamster has been architecture critic since 2013, reported that Pei’s masterfully unconventional City Hall, after decades of deferred maintenance, needs repairs and updates estimated at $100 million or higher. The debate over the future of the Brutalist design, the story noted, comes “as the Dallas Mavericks search for a site to build a new arena—and some see the government building’s plot as prime real estate.”

The paper’s editorial page then endorsed the possibility of moving city staffers to new digs, knocking down the Pei building, and redeveloping the site. “We need the chance to dream about this space being truly active and filled with public amenities in a way it isn’t now,” the editorial argued. “Could that be a new arena or entertainment district? Could it be more residences to bring additional life to the core? The possibilities seem endless. If the space where City Hall sits can contribute to that in a greater way, we all have a responsibility to keep all our options open.” If it wasn’t quite a rubber stamp for the demolition idea, it was pretty close. The possibilities seem endless!

Lamster quickly fired back. The destruction of the Pei building, he wrote in a cover story for the paper’s Sunday Arts & Life section, “would arguably represent the most egregious demolition of an American public building since New York’s Penn Station was torn down in the 1960s, an act of philistinism that essentially launched the modern preservation movement. Losing the building would also represent perhaps the biggest stain on the city’s reputation since the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.”

(Lamster is no Johnny-Come-Lately to the City Hall cause. In 2022, he wrote a tribute to Pei’s design with the following headline: “Why Dallas’ most hated building just might be its greatest masterpiece.”)

In recent days, the Dallas City Council has waded into the fray. I asked Lamster if he’d answer a few questions by email about where things stand. What follows has been lightly edited for clarity.

Punch List: The Dallas City Council began holding hearings this week to consider the future of City Hall. What’s the latest, and what’s the timeline for a final decision?

Mark Lamster: This whole situation materialized with extreme rapidity, and the future is disturbingly unclear. Much of the City Council seems bent on moving out of the building because of a large deferred maintenance bill, but there have been no comprehensive condition or structural assessments of the building, and the astronomical and wide-ranging cost estimates presented to the council by city staff seem exorbitant and unrealistic.

At one of the meetings you mentioned, there was a movement to fast-track serious studies of the building, and also its potential as an economic development site—with a clear emphasis on the latter option. After the public portion of the meeting concluded, the council went into executive session so it could discuss potential uses of the site behind closed doors. The lack of public accountability is deeply troubling. Meanwhile, in the last day we’ve learned that the council will retake the issue in the coming week. Things are unspooling at a breakneck pace.

The Pei building, like Boston’s City Hall, has always been a polarizing work of architecture, but what explains this new push to abandon it? Where did this plan come from?

That the building is, to put it politely, polarizing is not helpful, but style isn’t really the driving issue. The real problem is that Dallas doesn’t take care of its assets, with City Hall being just one example. That has left the building with a large (just how large is part of this debate) deferred maintenance bill at exactly the moment that a) the city is building a multi-billion convention center next door, and b) the Dallas Mavericks are looking for a site for a new arena. Because the convention center site is essentially contiguous with City Hall, the city’s development class would love to get their collective hands on it. I’m no conspiracy theorist, but I don’t think it’s an accident that the issue of deferred maintenance at City Hall just happened to arise when the Mavs began their arena search.

The atrium of Dallas City Hall. Photo by Mark Lamster

I’m reminded here of the debate over Trump’s White House ballroom. His supporters, and the president himself, often tout the fact that it’s going to be funded with private donations, saving taxpayer money. The problem, of course, is that raising private money for a White House ballroom opens all kinds of opportunities for corruption and pay-to-play schemes. In a broader sense, the debate reveals a near-total rejection on the right of the very idea of public money for public projects. Everything becomes a development opportunity.

I would not say it’s a right-left issue in Dallas, but there is definitely a through-line to the Trump ballroom in a general willingness to discard historic building to satisfy the venality of powerful interests.

Chronologically, and in terms of its sensibility, where does City Hall fall within Pei’s body of work? Can you describe some of the architectural features that give it its power?

It’s smack in the middle of Pei’s career, at a point after he had established a reputation as a significant force within the profession, but before he became the kind of name familiar to the general public. The building itself exhibits basically all of the characteristics that make Pei’s work so attractive: forceful geometry, dramatic interior spaces, and an almost magical ability to control concrete—he was obsessive about its color and quality, and when the sun shines on it, you can see the result.

The building is defined by its canted front, which allows for larger floor plates as you go up, the idea being not to clutter up the ground floor with offices and bureaucracy. When you arrive, there is lobby that leads you up to a soaring atrium that brings light to all of the floors. It’s an absolutely wonderful space.

Can you give us a quick primer on preservation protections in Dallas and what might become of City Hall were city employees to leave it?

Dallas has incredibly weak landmark protections, but earlier this year the city’s Landmark Commission did, thankfully and rightly, begin the process of designation for City Hall. When that process was initiated, it triggered a two-year moratorium on any alteration to the building without the commission’s approval. During the moratorium period, the commission is charged with putting together a report that either does or does not recommend landmarking of the building, and its finding, whatever it might be, would then have to go through a series of approvals, ending with a vote by the full City Council. Could the building be sold during that time? Probably. But the real danger is that the City Council or the City Attorney’s Office finds some legal justification or other political way of maneuvering around the moratorium.

A graphic that Docomomo, the Dallas chapter of the American Institute of Architects, and Preservation Dallas are distributing to help rally support to protect the building

City Hall was completed 47 years ago, in 1978. Typically legal protections and preservation advocacy both tend to focus on buildings that are 50 years old and older. But important works of architecture can fall out of fashion and become vulnerable to demolition well before that, often when they’re between 30 and 50. (This is an issue I focused on when I worked in the Mayor’s Office in LA. And I know that you’ve been writing about the virtues of Dallas City Hall for years, helping build a constituency for protecting it.) How can preservation groups get ahead of this curve and start making an effective case for younger buildings?

A few years ago I took part in a debate at Docomomo’s annual conference about whether the group should preserve only works from the modern period (its foundational mission) or expand its purview to include more recent work, most notably postmodern buildings, which many in the organization revile. I was pro-expansion, and I’m happy that the organization seems to be following that direction.

But with styles that are polarizing, like Brutalism and postmodernism, it can be a hard sell to the public. It certainly doesn’t help that preservation, generally, has become a lightning rod on the left, where some see it, and not without justification, as a force of gentrification and inequality. The antipathy toward anything that isn’t traditional—and especially Brutalist works—emanating from the White House is also deeply problematic.

We’re in this odd moment when we’re seeing a revival of interest in Brutalism—and even a wave of neo-Brutalist (or maybe Brutalist Adjacent) designs by architects like David Adjaye, Peter Zumthor, and Tod Williams and Billie Tsien—but also works like Dallas City Hall and the Vaillancourt Fountain in San Francisco in the crosshairs. Do you have any brilliant explanation for this seeming contradiction?

It’s certainly an odd moment. I think preservationists and historians can take some credit for the revival of interest. Boston recently landmarked its wonderful Brutalist City Hall, and I think the efforts to reframe the narrative around that building, focusing on the civic optimism and invention that it represented, were essential to that effort. The great visual drama of Brutalist buildings has made them catnip on social media, and that has certainly been helpful in introducing a new and appreciative audience.

If you had to guess today, what’s your prediction about what will happen to Dallas City Hall?

I am reluctant to make any guess as to the future. I am heartened by the public outcry in response to the situation, but Dallas has a long and sorry history of shooting itself in the foot and caving to the interests of developers. So it is definitely going to be a fight.

Punch List is published weekly. Subscribe free here, or sign up for a paid subscription, with bonus material, here.

Email: [email protected]

Reply