- Punch List Architecture Newsletter

- Posts

- It happened at Yale

It happened at Yale

Or did it? The manipulations, architectural and otherwise, of Luca Guadagnino’s “After the Hunt”

New Haven’s Three Sheets bar (as recreated in London), with Chloë Sevigny as Kim and Julia Roberts as Alma, in “After the Hunt.” Yannis Drakoulidis/Amazon MGM Studios

One of the most pointed moments in Luca Guadagnino’s “After the Hunt”—or maybe just one of the most trolling—comes in the movie’s opening seconds.

The words “It happened at Yale” flash onto the screen—a phrase that drew big and maybe anxious laughs at the recent screening I attended, which also happened at Yale (the auditorium at 53 Wall Street, to be exact, in an event hosted by the Yale Film Society and Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies).

The words lingered just long enough for me to wonder: Wait, isn’t that the Woody Allen typeface?

A minute or so later, when the title cards began to appear, all doubt disappeared: Yes, that’s the Woody Allen typeface (Windsor Light Condensed, for those keeping score at home, or something that looks an awful lot like it), and, yes, the entire title sequence is meant as an homage to the way Allen opens his films. And, yes, “After the Hunt,” which takes up the #MeToo moment as a central theme, launches itself with a winking tribute to one of that moment’s best-known exiles, as if to usher him lovingly back into the Hollywood fold.

It is certainly, as they say, a choice.

From there we rush headlong—or descend, really, given the film’s preference for murky, moody, cave-like, and very loud spaces—into the fray. (The cinematography, by Malik Hassan Sayeed, often seems to throw not illumination but mud in the direction of the actors, just as the sound design is frequently all too happy to pit the dialogue and the clanging, Hitchcock-like score, by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, against one another.) Here’s Julia Roberts as Alma Imhoff, who teaches philosophy at Yale. And Andrew Garfield as Hank Gibson, a colleague in her department who, like Alma, is waiting to hear about tenure. And, to round out the distended romantic triangle, Ayo Edebiri as Maggie Price, a grad student finishing up a dissertation on—you’ll never guess!—“the resurgence of virtue ethics.”

Ayo Edebiri (as a grad student in philosophy) and Julia Roberts (as one of her professors) green-screening it up near Long Island Sound. Yannis Drakoulidis/Amazon MGM Studios

My interest in writing about the movie is not to make sense of its grab-you-by-the-lapels symbolism or deeply confused politics. (Reader, those politics are really confused: sometimes pompously anti-woke, sometimes straining to critique the absurdity of so much recent anti-woke cocksureness.) Nor am I here to offer an assessment of the clear tension, some of it generational, between the script, the debut from screenwriter Nora Garrett, and the choices Guadagnino, 54, makes as director.

For that kind of analysis I will happily point you to reviews by Justin Chang, Alissa Wilkinson, and Stephanie Zacharek. It would be tough in any case to improve on this bit from Zacharek, on how the movie’s academics pontificate: “As you watch, you might think, as I did, that surely these people can’t go through the whole movie talking like this, in spiraling loops of jibber-jabber concerning the nature of free will, the role of individual morality within societal structures, and so on. Sadly, you would be wrong.”

I’m more intrigued by the film’s architectural set pieces—by how “After the Hunt” uses Yale’s campus to make its sometimes compelling and more often cudgel-like points. (Wilkinson: “Oh, did I mention, this is Yale? ‘After the Hunt’ is the most Yale, a movie so Yale-y that the first words onscreen are ‘it happened at Yale,’ though the ‘it,’ as it turns out, is nothing to boast about.”) Guadagnino, after all, has a track record of using architecture as effectively and evocatively as any living film director. This was especially true in his earliest movies, including, from 2009, “I Am Love” (set in an exquisite 1930s Milanese villa by Piero Portaluppi); “Call Me by Your Name” (2017); and “A Bigger Splash” (2015). Even his uneven recent output, from “Challengers” to “Bones and All,” has been marked by a remarkable visual and spatial keenness.

Gustave Courbet, “After the Hunt,” oil on canvas, ca. 1859

In “After the Hunt,” he has an especially rich vein to mine: the architecture, from the neo-Gothic to the severely modernist, of the central Yale campus. There is a big asterisk attached to the movie’s setting, though: It was shot entirely in the UK. (As Roberts told Variety, Guadagnino “built Yale in London.”) It is green screen magic that gives the impression that Alma is walking across Beinecke Plaza or consoling Maggie as she sits against the base of a tree on Old Campus, under the statue of Abraham Pierson, whose visage, rather forbearing in the real-life monument, is digitally contorted onscreen into a rigid mask of puritanical judgment.

This means that the line in Allenesque type we see at the start of the film—“It happened at Yale”—is, at least in literal terms, not true, as one of my fellow attendees at the Tuesday event pointed out during a post-screening discussion. It also means that Guadagnino can manipulate the film’s architectural settings essentially at will, with a kind of digital ease that just wouldn’t have been possible had he been obliged to steer a battalion of trucks through the narrow streets of downtown New Haven; set up cameras, lighting, boom operators, and craft services at the foot of Vanderbilt or Connecticut Hall; and find a block of rooms for cast and crew at the Study.

The director takes advantage of this freedom to deposit his characters, in addition to the scenes on Old Campus, in three especially recognizable corners of the New Haven chessboard: a bar called Three Sheets, the Indian restaurant Tandoor, and Beinecke Plaza. The scenes in Three Sheets (“The Elm City's Friendly Neighborhood Gastrodive”) drew the loudest reaction during the screening I attended, which was packed with students. But it’s on Beinecke where Guadagnino and Garrett can most fully indulge their fantasies about faculty members verbally unloading on snowflake students and, spoiler alert, explore what happens when the students fight back.

I, too, like to sit cross-legged atop the desk in my Yale classroom to discuss “autonomy” and “happiness.” (Actually almost none of the classrooms have desks like this—just big tables around which everybody sits. This is some “Mona Lisa Smile” b.s.) Yannis Drakoulidis/Amazon MGM Studios

“After the Hunt” is set in the period just before the pandemic. It is eager to relitigate, to use a phrase unfortunately popular in those days, the debates that flared up on college campuses between 2015 and 2020 on subjects including but not limited to race, class, sexual violence, and gender identity. (At Yale there was also the Great Halloween Costume Upheaval, a very big and serious deal at the time.) When Guadagnino wants to ratchet up the tension, or set one character against one another in a public squabble, or position a chanting group of sign-waving students around Alma in a tight and threatening circle, he shoves them all onto Beinecke Plaza—or, better yet, he squeezes them near or under the dramatic overhang of Beinecke Library, a masterpiece of high modern rationalism completed in 1963 that, while wondrous inside, is rather chilly and hard-edged on its exterior. Once the characters are trapped there, we viewers can better understand how heavily the weight of shame, failure, anger, and the history of Yale as an institution are conspiring to press down on their comparatively tiny shoulders.

I was reminded of what the architectural historian Vincent Scully wrote about the library, in the 2004 book “Yale in New Haven”: that “the Beinecke does embody a kind of frigid perfection. There it is on the empty plaza that was sterilized for it by its architect, Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill.”

Scully’s brilliant personal and political response to that sterility was to help commission, in league with a group of architecture students and younger faculty and as a satirical statement against the Vietnam War, a sculpture by Claes Oldenburg (Yale College class of 1950) called “Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks.” The group, calling itself the Colossal Keepsake Corporation of Connecticut, dragged the artwork onto Beinecke Plaza in the spring of 1969, right under the window of the Yale president’s office, where it became the backdrop for a series of anti-war protests. It was later moved to Eero Saarinen’s Morse College, where my senior-year dorm room looked directly onto it.

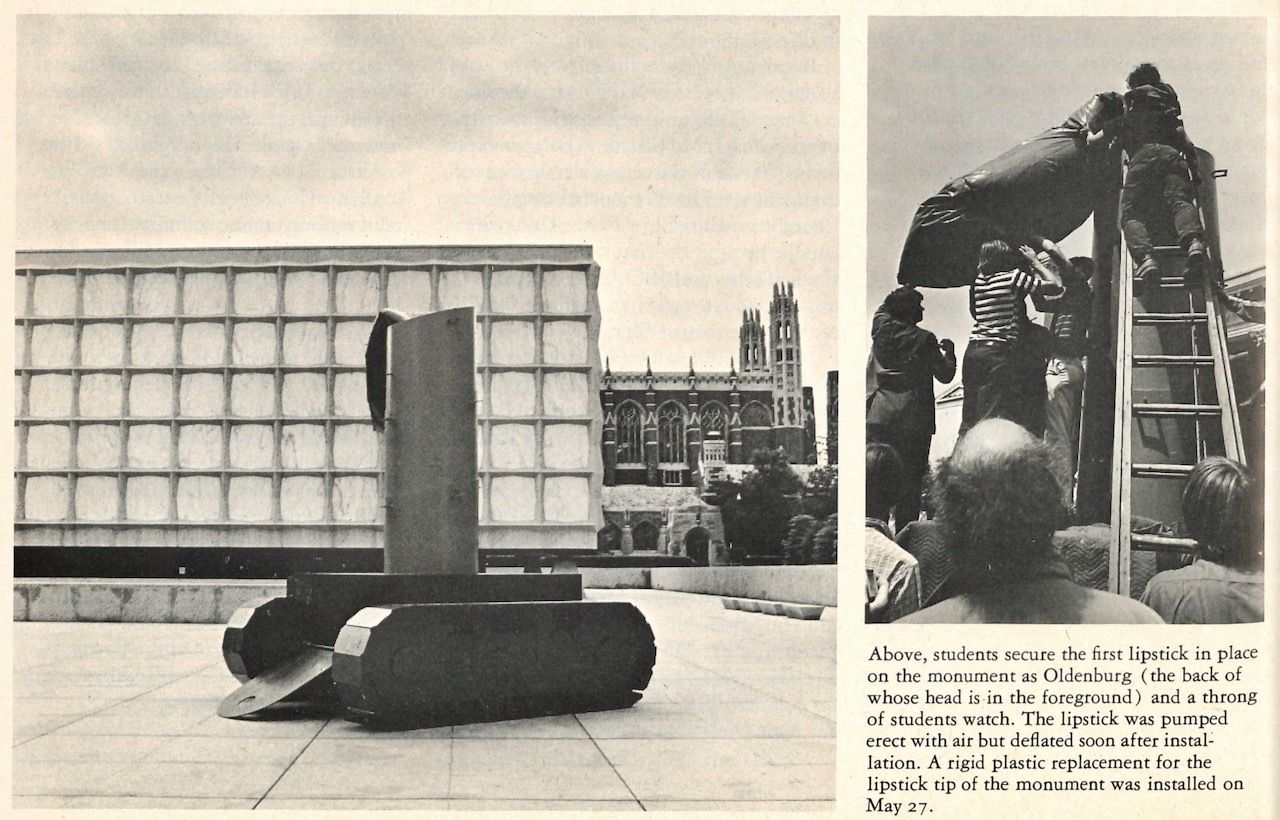

An item in the Yale Alumni Magazine, June 1969, showing Oldenburg’s Lipstick as originally installed (and initially limp) in front of Beinecke Library, quite near the location of the most pivotal scenes in “After the Hunt”

The Lipstick combined a severe tank-like base of weathering steel with an inflatable shaft in the form of a lipstick tube. At first Oldenburg and his crew couldn’t manage to inflate the tube all the way, so it kept flopping over. It was really this combination—the phallic and the pathetic, the hard and the soft, the expert and the amateur—that made the piece work. As Scully later wrote, the Lipstick “was not designed as a museum piece but as an active if ironic warrior in the gentle culture wars.”

A little bit of that spirit—the irony, especially, but also offering up even the possibility of a gentle culture war instead of our current loud, dumb, and histrionic version—would go a long way in “After the Hunt.”

But let’s give Oldenburg the last word. His career-long aim, as he put it in 1961, was to produce “an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.” An art, he continued, “that imitates the human, that is comic, [or] violent, or whatever is necessary.”

Punch List is published weekly. Subscribe free here, or sign up for a paid subscription, with bonus material, here.

Email: [email protected]

Reply