- Punch List Architecture Newsletter

- Posts

- A soundtrack with (virtually) no narration: L.A. gathers to remember Frank Gehry

A soundtrack with (virtually) no narration: L.A. gathers to remember Frank Gehry

Warning: This one’s a bit more gossipy than usual. Plus: The White House ballroom gets a sham hearing; the hero of “Free Solo” goes architectural; and California Forever is back!

Herbie Hancock at Frank Gehry’s lime-green piano. “He could make a masterpiece out of a piece of paper that’s crumpled up,” Hancock said of the architect, in a remark that drew groans from my section

Appearing in this dispatch: Thom Mayne, Blythe Alison-Mayne, Herbie Hancock, Michael Maltzan, Alan Cumming, Cecily Brown, Cathleen McGuigan, Deborah Borda, Alex Ross, Dana Cuff, Greg Lynn, Sylvia Lavin, Peter Sellars, Yuval Sharon, Joseph Giovannini

I sometimes use Frank Gehry in my courses on architecture and writing as a sort of reverse example: He was the architect who didn’t write. In fact there was more (which is to say less) to it than that. Gehry made a career-long point of refusing to lean on theory to justify his more outré adventures in form-making or material experiment, concentrating instead on letting his buildings speak, or argue, for themselves. (“He distrusts words,” as Herbert Muschamp wrote.) To a certain extent this was an act, at least the self-deprecating part of it, the who-me, aw-shucks disavowal of strategic intent. Gehry was the canniest architect I’ve ever met by a wide margin, and probably the most astute packager of his own legend. But he was also not a great talker, at least in public settings, and his lectures could be downright terrible.

And so it made a poetic kind of sense that “Music for Frank,” a moving sonic memorial that Gehry’s office and the Los Angeles Philharmonic organized Tuesday evening at Walt Disney Concert Hall, was for nearly all of its two-hour running time a soundtrack without narration. The conductors Esa-Pekka Salonen and Gustavo Dudamel offered quick remembrances of their friendships with Gehry between musical selections—with Dudamel using his pet name for the architect, “Pancho,” the Spanish nickname for Francisco—as did Herbie Hancock. But this invitation-only affair, which nearly filled Disney Hall’s 2,265 seats, contained no formal speeches, and almost no mention of the architecture profession or Gehry’s place in it.

This, too, was fitting. Gehry spent the first half of his career hanging out with visual artists (Chuck Arnoldi, Billy Al Bengston, Larry Bell, Ed Moses) and the second half with people in the music world (conductors, composers, and critics especially). When my wife Rachel (trained as a classical pianist) and I would run into him and his wife, Berta, it was typically at a musical rather than an architectural gathering: at the L.A. Phil or nearly as often the Ojai Music Festival, where Frank was a regular presence despite carrying a grudge that he wasn’t picked to redesign Libbey Bowl, the spot where the event has been held since 1952. And when we saw him in those locales, mostly what he wanted to do was talk about music.

With fellow architects Frank’s relationships were fraught, marked by competitiveness and occasionally suspicion. When L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art mounted a survey of recent work by local architects in 2013 under the shudderingly awful title “A New Sculpturalism”—a show that after much chaos wound up being curated by Thom Mayne and Morphosis—Gehry at first refused to be included and then agreed on the condition that his office be represented by a single project (its second-place competition entry for the National Museum of China) shown in its own separate gallery. Gehry virtually never used the power he wielded in Los Angeles civic affairs to add younger architects to his largest projects, such as the mixed-use Grand Avenue development across from Disney Hall or the countywide master plan for the L.A. River.

This anxious traffic ran both ways. Architects grouped together with Gehry by historians or critics under the loose banner of the “L.A. School” sometimes rejected the label as aggressively as Gehry did; they understandably chafed at the notion that the older architect operated as benevolent dean or godfather of the local scene. “The first time I heard of Frank Gehry I was 38 years old,” Thom Mayne once said, however questionable his math may seem to us now.

Those personal histories were legible even in the seating chart for Tuesday night’s event. (We all had assigned seats.) As far as I could tell, the only architect placed in the immediate vicinity of Berta and the rest of the family, about two-thirds of the way up the orchestra section, was Greg Lynn (along with his wife, the architectural historian Sylvia Lavin). Lynn is a mensch, but I think it would be fair to say that Gehry never had reason to see him as a professional rival in any sense; Lavin meanwhile has notably saved her most acerbic commentary for architects other than Gehry. Deborah Borda, the former CEO of both the Los Angeles and New York philharmonics, was in this section, as were Broad museum director Joanne Heyler, actor Alan Cumming, and the arts patrons Jerry and Terri Kohl. New Yorker music critic Alex Ross was in his usual spot at the top of the orchestra, near the aisle.

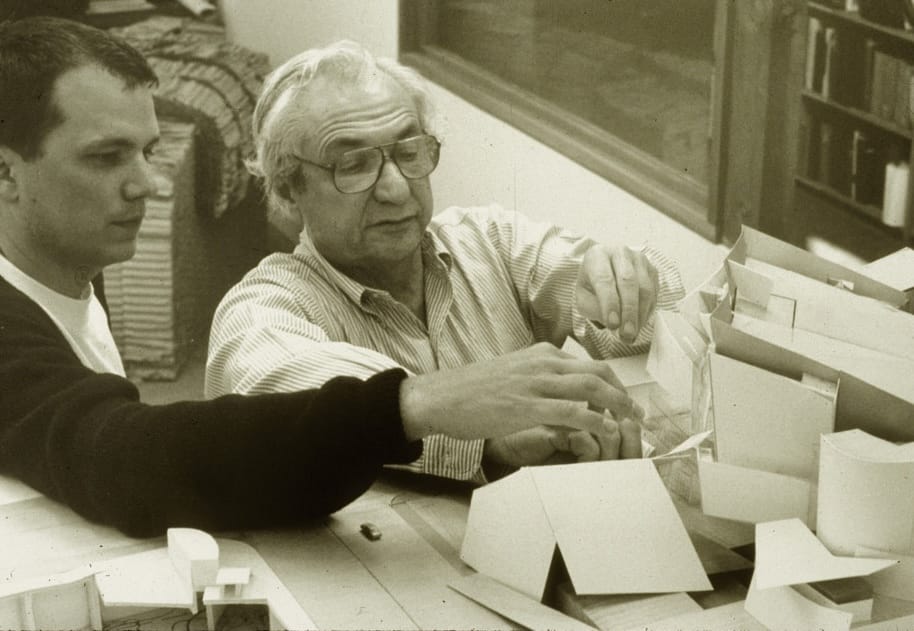

This photograph of a young Michael Maltzan working with Frank Gehry on a Disney Hall model, circa 1990, was included in the “Music for Frank” program

Just to the left of the family, in a sliver of a section knifing down toward the stage, were the musicians: Dudamel and Hancock when they weren’t onstage, along with the composer John Adams (whose “Wild Nights” section of “Harmonium,” a 1980 choral-orchestral setting of Donne and Dickinson poems, was for me the highlight of the program); the L.A. Master Chorale artistic director Grant Gershon; the opera director Yuval Sharon; and the impresario Peter Sellars.

The architects and the architecture critics were meanwhile packed together, like crabs in an upholstered bucket, in a low balcony next to the musicians. I was seated here, directly adjacent to Thom Mayne and his wife, Blythe Alison-Mayne, which seemed like some sort of cosmic joke from Gehry given the contentious relationship Mayne and I have had (have enjoyed?) over the years. Blythe sat between us as a buffer and could not have been more gracious. Mayne, for his part, wanted to talk about how unfair he found Robert McFadden’s New York Times obituary of Bob Stern—how odd he thought it was that the article focused so much on the price tags of apartments in Stern’s buildings. (I don’t think he’s wrong about that.)

Directly in front of me were two former SCI-Arc directors (Eric Owen Moss and Hernan Diaz Alonso) as well as the architectural historian Todd Gannon and the architect Mohamed Sharif. (Moss spent some time talking with my plus-one, the USC history professor Bill Deverell, about the architect’s son Miller, a former USC and Louisville quarterback who is now prepping for the NFL draft.) UCLA’s Dana Cuff and the architect Kevin Daly were a couple of rows down, alongside Craig Hodgetts, Ming Fung, and the former Architectural Record editor and Newsweek critic Cathleen McGuigan. The writer and critic Michael Webb (who halfway through the concert would use his program to jab Sharif for pulling out his cell phone once too often) was a few seats to the right of me. The critic Joseph Giovannini (whose aggressive yearslong campaign against Peter Zumthor’s LACMA design was, in case you never realized, in part a proxy fight on behalf of the idea that Gehry should have been given the job) was just behind. I ran into Michael Maltzan, who spent the early part of his career in Gehry’s firm, out by the box office before the show but didn’t see where he wound up sitting. I spotted the painter Cecily Brown, who’s married to the architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff, but not Ouroussoff himself.

(I’d have more names to drop but I had to run soon after the event ended to catch a red-eye back to JFK.)

As for the program itself, I marveled at Hancock’s virtuoso improvisation, which he performed on Gehry’s own lime-green Steinway. (Hancock “invented a Debussy Prelude on the spot,” as Alex Ross put it to me in an email.) But I cringed a bit when the musician, in his introductory remarks about his friendship with Gehry, said that the architect produced daring forms by a similar kind of improv. “He could make a masterpiece out of a piece of paper that’s crumpled up,” said Hancock, after which I’m pretty sure I heard Thom Mayne groan. I sympathized: This is a hoary notion that flattens architecture into an unimaginative (not to mention inaccurate) caricature. It has its roots in Gehry’s 2005 turn in animated form on The Simpsons—an appearance “that has haunted me,” the architect told Fareed Zakaria. It popped up again in Sydney Pollack’s documentary “Sketches of Frank Gehry,” released the following year. Improvisation might have been a metaphorical goal that Gehry chased throughout his career, an ambition that helps explain why he was so drawn to musicians and visual artists. But that’s hardly the same as saying he literally made architecture that way.

When he first pulled out of the MOCA show, for instance, only to agree later to return under a raft of conditions, Gehry told me as much: “I’m subject to misunderstanding about the seriousness of my work. People assume I am just crumpling paper and so forth. This was feeling a bit that way, a trivialization.”

The program cover featured an artwork (Razzle #4 “Close Up”) by Alejandro Gehry, one of the architect’s sons

On the whole, though, the remarkable, touching event served both to honor Gehry’s obsession with music and allow Disney Hall to radiate its substantial charm and sophistication directly, without having to compete with extended speechifying about the architect’s place in history. The concert hall, in my view, is Gehry’s finest single achievement: for its civic spirit, filling a literal and metaphorical hole at the top of urban renewal–ravaged Bunker Hill, as well as its warmheartedness, small-d democratic sensibility, spatial appeal, and (thanks to Gehry’s collaboration with Yasuhisa Toyota) acoustical brilliance.

On the very short list of venues where the city comes together in genuinely communal fashion, it is matched only by Dodger Stadium and the Hollywood Bowl. As far as interior L.A. spaces go—rooms with a roof—it has no rival.

On the topic of architects and language, finally, I’m reminded of something Ada Louise Huxtable once said: “The architect, in particular, can be close to totally inarticulate and frequently is; usually the better he is the less he has to say, and the more off-putting it is when he says it.”

News & Notes

“Sentimental Value,” which earned nine Oscar nominations this week, “is an excellent lamp movie.”

The White House ballroom went before the Commission on Fine Arts yesterday, a hearing that was delayed in order to make sure President Trump’s new appointees would be in place to cheerlead for the project. (James McCrery, one of those freshly seated commissioners and the original ballroom architect before being replaced by Shalom Baranes, recused himself from discussions of the design.) The new chair, Rodney Mims Cook Jr., said this during the hearing: “We need to let the president do his job, and, as best we can, keep his mind off of things like this, that we can keep him rolling, and do it as elegantly and beautifully as the American people deserve for generations and further centuries into the future.” (Who says oversight is dead?) Meanwhile, a federal judge, Richard Leon, expressed some doubt that Trump has the legal authority to proceed with the project, ahead of an expected ruling next month. Leon described the government’s case defending the ballroom as a “Rube Goldberg contraption.”

The architecture-free solo mashup we’ve been waiting for is here: Assuming the weather cooperates, Alex Honnold will climb Taipei 101, at 1,667 feet the eleventh tallest building in the world, on Netflix at 8 p.m. tonight Eastern time, in an event called “Skyscraper Live.” Honnold told the New York Times that the 2004 tower is “a perfect climbing objective in that the spectacular climbing is uncontrived. The easiest way up the building is also the coolest way up the building. You’re pinching the very outer edge, climbing over these ornamental dragon heads. There are a bunch of features on the building that just make it insanely fun, like a jungle gym, in that the holds are wide pinches that feel comfortable in your hand.”

Architecture billings remained weak in the U.S. to end the year.

California Forever, the Silicon Valley-backed project to build a new city from scratch on farmland between the Bay Area and Sacramento, has reappeared 18 months after a stillborn ballot measure to trumpet new agreements with local building trades: “The land is ready. The plans are ready. The workers are ready.”

See you next week!

Punch List is published weekly. Subscribe free here, or sign up for a paid subscription, with bonus material, here.

Email: [email protected]

Reply